topics

topics

download media

download media

search

search

| 1500 - 1847 | 1848 - 1919 | 1920 - 1959 | 1960 - 1999 | 2000 - 2020 |

Changes Abound 1920 - 1959

What would you like to find?

Downloadable Media: Changes Abound

Imagery

The Roaring 20s were an era of wealth and consumerism across the United States. It was a time of hope, prosperity, and cultural change. With the economy and the stock market booming, people were spending money on entertainment and consumer goods; however, the wealth and good fortune that much of the country experienced was not universal.

Land of Plenty...?

California, 1920: A growing agricultural industry, connected to the rest of the U.S. by railroad tracks. There were more than 115,000 farms spread across the state, with 29.4 million acres of farmland in total. Fruit production in particular was highly successful throughout the decade, as apples, peaches, pear, and plums were all highly successful crops.

While the rest of the country enjoyed the “Roaring Twenties” and the stock market boomed, farmers experienced continual cycles of debt, specifically due to falling product prices. In addition, the process of transitioning from animal labor (horses and mules) to machines was costly and contributed to farmers’ financial woes.

Questions

What contributed to the low prices for agricultural products?

Why were farmers struggling financially when the rest of the country was experiencing a financial boom?

US Farm Census

California Department of Food and Agriculture Founded

In 1919, the California Legislature created the Department of Food and Agriculture, responsible for protecting and promoting agriculture. Today’s California Department of Food and Agriculture now has five separate divisions that provide services to producers, sellers, and the public.

Questions

Why was the CDFA needed?

What issues were likely occurring?

California Department of Food and Agriculture

On January 16, 1919, the 18th Amendment, prohibiting the "manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors," was ratified. The Volstead Act, which would provide for enforcement of the Amendment, was passed one year later in 1920.

Library of Congress, "18th Amendment"

Wineries Decline, 1919-1933

The National Prohibition Act, known informally as the Volstead Act, was enacted to carry out the intent of the 18th Amendment—prohibiting the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages in the United States. These policies challenged California’s booming wine industry. In 1919, there were approximately 700 wineries operating in the state and 300,000 acres of wine grapes in production. The fourteen years of Prohibition would cause a sharp decline in the number of California wineries, leaving just 388 left in operation.

Those 388 wineries survived thanks to a combination of transportation loopholes, and religious exceptions, along with bootlegging. A legal loophole at the beginning of Prohibition provided a transportation loophole, wherein the wine grapes could be transported to other U.S. states for home wine making processes via railroad. While these grapes were of lower quality and produced subpar wine, this option allowed wine grape producers a source of income.

Other wineries turned to producing sacramental wines, used for religious purposes, to avoid the legal restrictions on winemaking and transportation of wines. Still others would continue to operate and rely on bootleggers to transport their wines and keep them in business.

Questions

How did wineries and grape growers get around the legal restrictions on sales?

How did the growth of the railroad help keep the wine grape market afloat?

A. Borg, "A short history on wine making in California," UC Davis Library, 2016

The Industrial Revolution and associated growth of cities and factories drew attention to the dangers of working in a factory. U.S. legislators tried to protect workers through a series of labor laws, to mixed effects.

Agricultural Strikes, 1933

California farm laborers participated in strikes throughout the 1930s to demonstrate the need for better pay and working conditions. As the Great Depression continued, agricultural workers felt the strain of low wages in combination with the high price of living. Striker Augstine Ramos remembers the following: "In those days only the poor people worked for the farmers, the big shots. They were getting paid very low wages—people couldn't make a living any more. That prompted people; as small as they were, as unorganized as they were, they had something in common. They got together and went on strike."

Below are summaries of some of the agricultural strikes in California during 1933:

-

El Monte Fruit Berry Strike: In May, a strike was called by the approximately 600 Mexican berry pickers employed by Japanese growers in the San Gabriel Valley. The Cannery and Agricultural Workers Industrial Union (CAWIU) organized workers and presented demands for higher, more consistent wages. By June, the strike had grown to include other agricultural camps, including vegetable farms, and approximately 7,000 workers. The union settled with the growers in mid-July for increases of twenty-five cents for men and twenty cents for women. But because most of the crop had already been picked by scab (temporary, non-unionized) labor, the majority of the workers were unable to benefit from the settlement.

-

Santa Clara County Cherry Strike: In June, the CAWIU organized a total of 1,000 cherry pickers across 20 ranches in Santa Clara County and presented demands for higher pay. By the middle of June, many of the major growers gave into the demands of the picketers, as the fear of losing their crops was apparent. The hourly wage of workers was successfully increased from 20 cents per hour to 30 cents per hour.

-

San Joaquin Valley Cotton Strikes: In the month of October, California’s Central Valley was rocked by a labor strike that paralyzed cotton farming operations in several counties. The conflict involved 12,000-19,000 workers, held up harvesting for almost four weeks, and threatened to impede the harvesting of the state’s cotton crop which was valued at more than $50 million. The strike was instituted because the cotton growers rejected the workers’ demands for an increase in wages from sixty cents to $1.00 per hundred pounds. Although the union finally settled for a lower pay rate of seventy-five cents, the strike was considered a victory for the workers. This strike would go down in history as the largest strike in the history of American agriculture.

All told, more than 47,500 farmworkers participated in the 1933 strikes. Twenty-four of these strikes, involving approximately 37,500 workers, were under the leadership of the CAWIU. Twenty of the CAWIU-led strikes resulted in partial wage increases while only four strikes ended in total defeat for the union.

Questions

What were the main complaints of agricultural laborers?

What were some safety concerns for farm work?

Quote: Melquiades Fernandez, "Bittersweet Fruit: El Monte's Berry Strike of 1933," April 7, 2015, KCET.org ; Strike Information: Kate Bronfenbrenner, "California Farmworkers' Strikes of 1933," in R.L. Filippelli's Labor Conflict in the United States: An E

Agricultural Laborers Excluded from Labor Laws, 1935

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also called the Wagner Act, is a U.S. labor law guaranteeing the right of private sector employees to organize into trade unions, engage in collective bargaining, and take collective action (like organizing a strike). However, this act had several exclusions, including government workers, railway and airline industry employees, domestic workers, independent contractors, and farm workers. The exclusion of farm workers was a source of ongoing conflict between farmers and their employees as laborers tried to obtain better pay and working conditions.

The Social Security Act of 1935, a law “which will give some measure of protection to the average citizen and to his family against the loss of a job and against poverty-ridden old age,” also excluded both agricultural and domestic workers.

Questions

Why were farm workers excluded from legal protections?

What types of protections did factory workers receive from these laws?

"National Labor Relations Act" from the National Labor Relations Board ; Quote: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Message of the President to Congress, June 8, 1934, U.S. Social Security Administration

Laborers Request Better Conditions, 1930s

Beginning in the early 1930s, labor moved toward the cities. In response, farmers and producers increasingly hired immigrant or migrant workers. Farmers, seeking ways to increase profits and limit costs, offered less pay and lackluster conditions to these workers. In response, farmworkers followed the example of factory workers in the cities and began to unionize.

Unions provided the option to bargain as a collective and often resulted in better pay and conditions. Farmworkers unions generally sought better wages and improved working conditions, including portable field toilets, cold drinking water, and compensation for workers injured on the job.

By today’s standards, these all appear to be reasonable requests, but legal protections for workers were lacking and often not enforced, especially in rural farming areas. When farmers and corporations refused to grant these requests, some agricultural workers would strike and refuse to work.

Questions

What were living conditions like for farm workers?

How did growers and farmers respond to laborers seeking better working and living conditions?

California State Archives

Agriculture in 1900 was fully dependent on animal power. By 1920, over 10% of California farms had tractors. In 1925, nearly 20% of California farms had tractors. Pacific Coast farmers enjoyed the benefits of a local farm implement industry. Inventors designed and perfected prototypes that California farmers had access to first, which would then be marketed and sold to the rest of the country and to the world. Grain combines, track-laying tractors, tomato pickers, and sugar beet harvesters were all developed in California’s machine shops.

The development of mechanized farming equipment was centralized in California due to many factors. Large scale farming across California allowed farmers to justify the costs of expensive equipment. The issues with steady labor forces, due to regulations on immigration and labor strikes, meant that farmers needed to find labor-saving options. Long dry seasons allowed tractors to run for longer days and more months of the year.

By the end of WWII in 1945, over 2.4 million tractors were in operation on farms across the U.S. Farmers had realized that the best way to handle the labor shortage and increased production demands was to mechanize as many processes as possible, making farming less labor intensive. Instead of needing multiple horses and multiple laborers to plant a field, a tractor could do the same amount of work in a fraction of the time. Tractors were also more cost effective—although expensive upfront, they did not cost as much as wages for multiple laborers over extended periods of time. In 1951, over 50% of California’s crops were harvested mechanically, and half of the country’s farm machinery was located in California. By the 1960s, mechanical harvesting in crops was routine for farmers across the U.S.

Musoke & Olmstead, 1982

Dairy Industry Booms, 1940s

The 1940s were significant for many reasons, including the massive number of inventions and innovations that came out of increased demands and strains on the US because of WWII. Included in these inventions and innovations were different tanks, pumps, and machinery that were repurposed by dairy farmers to create more efficient and productive ways to milk their cattle.

The first commercial automated milking system was sold in 1948 and could not have come at a better time—selective breeding practices had increased milk productivity rates in dairy cattle and farmers were having a hard time keeping up. Instead of milking by hand and bottling the milk themselves, farmers used automatic pumps and stainless steel tanks to store the milk.

Questions

How could the mechanization of the dairy industry benefit the average American citizen?

"Landmarks in the US Dairy Industry", USDA Report

The stock market crashed in October of 1929 and sent Wall Street and investors into a panic. As a result, millions of people lost their money as banks across the country crashed and closed. The downturn in spending and investments caused factories and businesses to slow production and begin firing employees. For those lucky enough to keep their jobs, wages fell, and the value of their pay declined significantly.

Although the Great Depression hit every part of the country hard, California’s agriculture industry continued to grow. San Joaquin Valley growers would quadruple their acreage during the mid-1930s. The demand for workers, and for wages, continued to increase. California’s cotton producers paid almost 50% more for picking cotton than farms in the Southern U.S.

California Capitol Museum, "The Dust Bowl, California, and the Politics of Hard Times" ; History.com "The Great Depression"

Severe drought hit the Midwest and Southern Great Plains in 1930. As crops failed, and without deep-rooted prairie grasses to hold the soil in place, the soil began to blow away. Eroding soil led to massive dust storms and economic devastation—especially in the Southern Plains. The Dust Bowl lasted for about a decade, but its long-term economic impacts on the region lingered much longer.

Roughly 2.5 million people left the Dust Bowl states of the Midwest—one of the largest migrations in American history. California’s climate, unemployment relief benefits, and the potential for agricultural work attracted Dust Bowl migrants. Between 1935 and 1940, approximately 250,000 “Okies” (a nickname for all Dust Bowl migrants, regardless of their actual home state) moved to California. More than 100,000 Okies would settle in Los Angeles and the surrounding region, while 70,000 would make their home in the San Joaquin Valley.

Okies Oust Immigrants, 1935-1940

Immigrant farm workers did the bulk of farm work in California during the early 20th century. A large number of these immigrant workers were Mexican, and actually lived in a migratory pattern—working in California for the harvest season, heading home to Mexico for the winter months, then returning to work in the fields in the spring.

However, the Great Depression and financial hardships disturbed this system, as more and more U.S. citizens needed jobs. Immigration legislation became more strict, resulting in the deportation of thousands of migrant workers. The influx of Dust Bowl migrants, or “Okies,” would fill many of the available agriculture positions, but there were not enough jobs for the number of people flooding into California.

In addition, the Okies, desperate for employment, would willingly take the jobs that farmworkers were leaving in order to strike. Unionization, meant to unite farm workers across the state to demonstrate the need for better pay and working conditions, meant nothing to the Okies, who would cross the picket lines and work for reduced pay.

Questions

What was the motivation for Okies to travel west, and especially to California?

Why would farmers and government officials prefer to have the Okies working on farms rather than keeping the traditional migrant labor system in place?

Library of Congress; California Capitol Museum

The New Deal was a series of government policies and programs implemented during President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's (FDR) first term. FDR took office in 1933 and had the difficult task of trying to pull the United States out of the Great Depression. The New Deal included policies and programs intended to aid workers, the homeless, farmers, and business owners.

History.com "Dust Bowl", California Capitol Museum, "The Dust Bowl, California, and the Politics of Hard Times" Exhibit

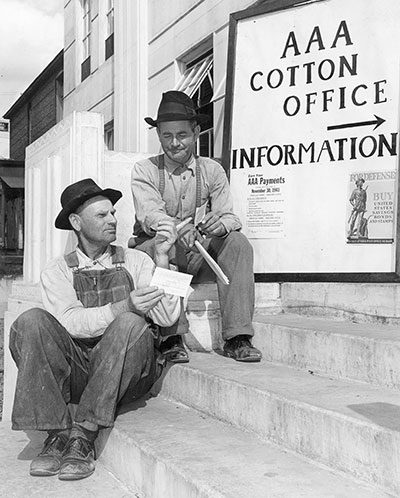

Agricultural Adjustment Act, 1933-1942

Large agricultural surpluses during the 1920s caused prices for farm products to steadily decrease, and the Great Depression caused agricultural markets to crash. The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) was signed into law by President Franklin Roosevelt on May 12, 1933. The goals of the AAA included limiting crop production, reducing stock numbers, and refinancing mortgages with terms more favorable to struggling farmers. At the beginning, this process seemed counterintuitive as fields were plowed under and corn burned as fuel instead of being used as food. However, removing surplus products from the market and paying farmers to reduce production of cotton, corn, and wheat, resulted in farm prices rising.

Farm income in 1935 was 50% higher than in 1932, and the trend continued throughout the 1930s. While the administration of the Agricultural Adjustment Act ended in 1942, federal farm support programs that emerged during this period would continue long after the war.

Questions

What was the public perception of the AAA's actions?

How could the problem of excess production and extremely low prices have been handled better?

The Living New Deal, livingnewdeal.org

Farm Security Administration, 1937

The Farm Security Administration, or FSA, established in 1937, attempted to reduce the impact of homelessness and migratory life on the millions of Americans displaced by the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. Instead of living in shanty towns or camps, the FSA set up clean residential camps with running water and simple but safe living quarters. The FSA hired photographers to document the work of the FSA and capture what rural poverty looked like in California and in other states, including the Deep South.

Questions

Before the FSA began building living quarters for displaced and migrant workers, where did they live?

What else did the FSA do?

Library of Congress

Social Security Act of 1935

Agricultural employment was not covered by State unemployment compensation laws or by Social Security benefits, but people living or working on farms might qualify for either under different circumstances. For example, men that worked on farms for the majority of the year but were hired for factory work during the winter months would be covered by both Social Security and State unemployment compensation laws. The requirements for both programs were fairly simple, so most people who found work outside of agriculture could qualify and receive the benefits once they reached retirement age.

Questions

How could agricultural workers qualify for Social Security benefits?

Why were they excluded from the program?

Social Security Administration History, July 1937

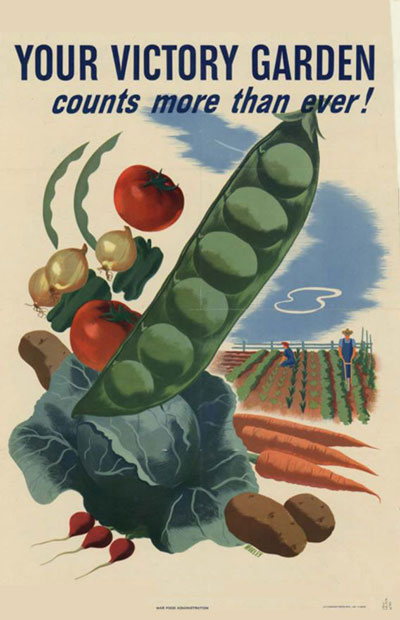

California was central to the country’s war effort. The state's fields and factories provided the most food and war material of any U.S. state.

Contributions from the Home Front, 1940-1945

California served as the country’s assembly line. With its large economic capacity (factories, railroad lines, shipping ports, and air travel) and massive population, the state began churning out various war supplies and equipment. Defense spending would boost local economies as well, assisting in the state’s recovery from the economic disaster of the Great Depression.

In addition, California supplied 14% of the nation’s total agricultural production, the most of any individual state. Agricultural income in 1940 amounted to $627 million and would increase to $1.7 billion in 1944.

Questions

In what ways could the average Americans contribute to the war effort?

What types of food and other consumables became hard, or even impossible, to buy in stores?

How did Victory Gardens help the war effort?

Capitol Museum, "Called to Action: California's Role in World War II" exhibit

Over ten million men would volunteer or be drafted over the country, meaning there were plenty of jobs that needed doing and few men left to do them. Six million women across the nation would join the workforce to fill these roles. Women became welders, riveters, and steamfitters in shipbuilding and aircraft manufacturing plants across California, building the vehicles needed for battle. In addition, women could also find employment as chemists, reporters, engineers, and hold non-combat military positions. In addition, women had to maintain a sense of normalcy at home, and became the heads of household while facing the potential that their male relatives might not return from war. Many women in rural areas became farmers in addition to their duties as mother and homemaker.

The Farmerettes Return, 1939-1945

The US Department of Agriculture’s Crop Corps, a federal agency tasked with overseeing agricultural efforts, monitored WWII’s Women’s Land Army of America, or WLAA. Approximately 1.5 million women would be employed through the WLAA to perform farming jobs including driving tractors, picking fruit, milking cows, and trucking produce. The WLAA allowed women to earn a living wage and learn valuable skills. The majority of women employed by the WLAA were seasonal farm employees.

Questions

What was the purpose of the Women's Land Army?

National Archives, "To the Rescue of the Crops" by Judy Barrett Litoff and David C. Smith (1993)

Railroadettes, 1939-1945

The Railroadettes were the railroad industry’s version of Rosie the Riveter. Railroadettes worked in many different positions for various U.S. railroads. Southern Pacific alone needed nearly 20,000 employees to replace male employees that joined the military during the war. White women took over many of the positions previously held by men, including white-collar positions like engineers and operators. Meanwhile, African American and Latina women worked in unskilled labor positions. According to an article in a February 25, 1943 edition of the Coronado Eagle and Journal, “[m]ore than 2200 railroadettes are now employed in the motive power and stores departments of the companys’ Pacific Lines.” Another source states that over 4,000 female employees had taken on jobs formerly done solely by men.

The California State Railroad Museum’s new digital exhibit “Crossing Lines: Women of the American Railroad” explores the Railroadettes and other notable women in the railroad industry.

Questions

What types of roles did female railroad employees fill?

Were they only working in traditionally 'female' jobs, or did they take jobs normally held by men?

California State Railroad Museum ; "More than 2,000 Women Now Employed by Local Railroad; More Needed," Coronado Eagle and Journal, Vol XXXI No. 8 Feb 25, 1943

1942 was a record-breaking year for agriculture. The Pacific states had huge crops to be harvested and limited labor to do so. Various organizations, including the YMCA, YWCA, Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, and others, worked to “help save the crops” and avoid massive amounts of waste. While adult day laborers, who could find their own transport and provide their own food were preferred, there were also small youth camps organized to feed and house groups of teens and young adults working during the harvest season.

Quote: Samuel I. Rosenman, ed., The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt (19381950), vol. 12, The Tide Turns, 1943, pp. 3437 ; "Women's Emergency Farm Service on the Pacific Coast in 1943," Bulletin of the Women's Bureau, No. 204 Publish

Women Fill the Labor Gap, 1940s

On January 12, 1943, otherwise known as Farm Mobilization Day, President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed the nation and stressed the importance of American agriculture in the efforts to win the war stating, “Food is the lifeline of the forces that fight for freedom. Free people everywhere can be grateful to the farm families that are making victory possible.” While many farm laborers during the war were men, women became a major source of farm labor and the efforts to keep both America and its allies fed.

In 1942, as many men left agricultural pursuits for better paying war industry jobs or for military service, various programs to recruit and train women for farm work began to appear across the U.S. In California, the American Women's Voluntary Services (AWVS) gathered one thousand women to help with fruit and vegetable harvests. A Vacaville farmer went to the AWVS and offered to hire women to work for him and a group of farmers, and that a camp was going to be set up at a local school to house the women. Some women employed at the camp were using vacation time from their formal employment while others were not regularly employed at the time.

In Southern California, the AVWS worked to recruit women but ran into an issue; many farmers were unwilling to hire women. Most farmers were used to hiring Mexican field laborers, who were migratory in nature and, according to social standards and customs, did not require the same quality of housing that a female workforce would require. Some farmers, willing to spend the money to supply decent housing in exchange for saving their crop, organized housing and bathroom facilities to suit the women’s needs. The most successful operation of this style, where the AWVS would recruit women for farm work and house them, was in the San Joaquin Valley, where women enjoyed excellent food, good housing, a bathroom with hot showers, and supervision by a camp director. These 1942 camps served as the blueprint for other female farm labor camps used during wartime.

Questions

Why were women filling farm labor roles?

Why weren't there enough male laborers to harvest the crops?

"Women's Emergency Farm Service on the Pacific Coast in 1943," Bulletin of the Women's Bureau, No. 204 Published by the US Department of Labor, 1945

In just five years, between 1940 and 1945, California’s population grew by 2.5 million people. In addition to a growing population, many non-skilled workers left the fields for military service or jobs in the growing war industry. An increasing number of jobs in defense plants allowed migrants from the Dust Bowl to leave field work behind in favor of higher pay and better conditions. The internment of Japanese Americans under Executive Order 9066 removed large numbers of Japanese farmers from their homes, and their fields, leaving many farms facing labor shortages and the threat of crop loss.

To read Executive Order 9066, click here.

The Bracero Program, 1942-1964

The Bracero Program was created by executive order in 1942 because many growers argued that World War II would bring labor shortages to low-paying agricultural jobs. On August 4, 1942, the U.S. and Mexico signed the Mexican Farm Labor Agreement, guaranteeing farm workers a minimum wage, insurance, and safe housing. In reality, farm owners frequently failed to live up to these requirements—strikes were a common occurrence throughout this period.

The introduction of the Bracero Program effectively reversed the immigrant laws and regulations of the 1930s, when migrant workers lost their jobs to the influx of Dust Bowl migrants. By the time the program ended in 1964, more than 4 million Mexican Braceros had entered the U.S. to work in the agriculture and railroad industries. These laborers especially helped the U.S. during WWII as the country struggled to meet both agricultural and industrial production demands.

Questions

Why did the U.S. decide to start the Bracero Program?

What were the key motivations?

Why did the program start in 1942 and not earlier or later in the war?

What was special about 1942?

Library of Congress; History.com

Japanese Internment, 1942-1945

Japanese immigration had taken off during the first half of the twentieth century. Many had become farm laborers, miners, or worked for railroad companies. Some farm laborers saved enough to purchase their own farmland and began developing new techniques to increase production. Japanese-American farmers produced more than 40% of California’s pre-war vegetable crop. According to a 1982 report, the average value of Japanese American-run farms in California was $280 per acre in comparison to the average $38 per acre for all farms.

In 1942, two months after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. The order called for the forced removal of all people of Japanese heritage to incarceration centers, where they were held until the end of the war. During the forced evacuations, many Japanese Americans could not quickly make arrangements for the safekeeping of their property—many lost their homes, farms, businesses, and belongings. Farm Security Administration records show that over 6,500 pieces of agricultural property, totaling more than 250,000 acres of land, were seized during the internment process.

Japanese Internment would officially end January 2, 1945 and Japanese Americans were allowed to return home. Farming families who had found lessees for their land often returned home to destruction, vandalism, or even total loss.

To learn more about Japanese Internment, and the experiences of Japanese Americans during WWII, visit https://outofthedesert.yale.edu/

Questions

What reasons did the U.S. Federal Government and Military give for Japanese internment?

What happened to the property (farms, shops, homes) that Japanese families left behind?

What was life like in internment camps?

National Archives ; Library of Congress ; A.V. Krebs, "Bitter Harvest," The Washington Post, Feb. 2, 1992

A broad range of scientific developments and technological advancements boosted agricultural production throughout the 20th century.

Pesticides, 1920-1960

While the introduction of pesticides in California had clear advantages, especially in preventing crop disease outbreaks, there was little understanding about proper use and harmful effects. Scientists and farmers worked together to develop regulations to keep food products safe for consumption.

The following information represents a summarized timeline of scientific and legal advancements regarding pesticides in the state of California:

-

1926: CDA (California Department of Agriculture) begins analyzing fresh fruits and vegetables for pesticides in response to public outcry over residues

-

1927: Chemical Spray Residue Act makes it illegal to ship, pack, and/or sell fruit or vegetables with harmful residues

-

1954: Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act amended to prohibit registration of any food-use pesticide that left residues UNLESS the FDA reported “safe” residue levels

-

1957: US Forest Service and Department of Ag prohibit spraying of DDT in areas around water in areas under federal jurisdiction

Questions

What were the positive impacts of increasing pesticide usage?

What were the potential dangers of early pesticides?

Why were there so many regulations placed on pesticides so quickly?

California Department of Pesticide Regulation, "A Brief History of Pesticide Regulation," published 2017

Nitrogen as Fertilizer, 1945

When the war ended, some of the technology that had been used for weapons, specifically explosives, would be repurposed to assist with growing crops. Instead of creating nitrogen for bombs, production facilities across the US would begin shipping ammonia nitrate to farms across the country. The ammonia nitrate would serve as an artificial source for the required nitrogen in soil, replenishing nutrients needed for plant growth and efficiency.

One such plant, the Shell Chemical Company Ammonia Processing Plant (pictured here), was located in California.

Questions

What was the original purpose of nitrogen production?

Why would processing plants be willing to change their focus entirely?

G. Hergert, et al. (2015) "WWII Nitrogen Production Issues in Age of Modern Fertilizers," CropWatch, Univ. of Nebraska

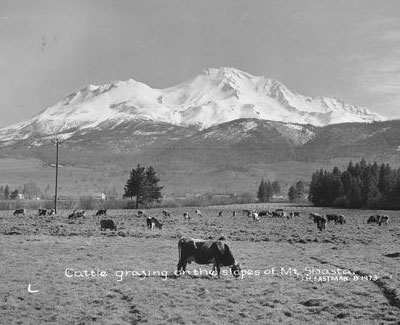

Selective Breeding Practices Begin, 1940s

Beginning in the 1940s, cattle ranchers experimented with selective breeding. By combining two different breeds with desirable traits, they discovered that some of the offspring would have the desired combination of traits (more muscle, better heat tolerance, etc.). DNA would not be discovered for nearly 20 years, but these ranchers were using their understanding of genetics and inheritance to create entirely new breeds of cattle. Selective breeding would increase productivity and prices for cattle producers.

The links between DNA and genetics would not be discovered by scientists for another 20 years.

Questions

What benefits did selective breeding bring to the cattle industry?

How were cattle improved?

What other animal species do you think have benefited from selective breeding practices?

livinghistoryfarm.org

On Christmas Eve in 1955, the Gum Tree Levee on the banks of the Feather River in Sutter County collapsed, sending massive amounts of water flooding into Yuba City. 40,000 people were evacuated and 38 died in the chaos. In the years following, California legislators would focus on the state’s water supply and how it would be managed.

The Burns Porter act, passed by the state’s legislature in 1959, authorized $1.75 billion for the State Water Project. The State Water Project would be responsible for flood control, generating power, and protecting (and sometimes creating) fish and wildlife habitats.

The State Water Project, still operating under that title today, is responsible for various water storage facilities, reservoirs, lakes, and pumping plants. The State Water Project also built and maintains hundreds of miles of canals and pipelines that move water throughout California, making sure that citizens and farmers alike have the water they need.

"Eel River and Feather River Floods, 1955" from militarymuseum.org