topics

topics

download media

download media

search

search

| 1500 - 1847 | 1848 - 1919 | 1920 - 1959 | 1960 - 1999 | 2000 - 2020 |

Moving Forward 1960 - 1999

What would you like to find?

Downloadable Media: Moving Forward

Imagery

As government regulations on pesticides and insecticides increased, agriculturalists and scientists worked together to develop new methods to control pests and protect crops.

Integrated Pest Management, 1950s

An emergence in pesticide use began after World War II. These new chemicals were inexpensive, effective, and enormously popular. However, it wasn't very long before a number of scientists working in pest management began to recognize these new pesticides were not to be the cure-all first envisioned.

In the 1950s, University or California researchers began to better understand pest control tactics (chemical, biological, cultural, physical, genetic, and even regulatory procedures) that could be employed to manage pests, but increased research was needed to focus on how these could be "integrated" into an effective, ecologically-based program.

The growing need for experts in this field created the role of Pest Control Advisers (PCAs) whose role is to advise farmers in managing pest control methods—the first licenses for PCAs were issued in 1971.

Questions

What does integrated pest management mean?

What career was created because of the development of IPM practices?

Frank G. Zalom, "California's Integrated Pest Management Program" from Radcliffe's IPM World Textbook

Mediterranean Fruit Fly Infestations, 1981

In 1981, the Mediterranean fruit fly infested the Santa Clara Valley. With California’s $14 million agriculture industry on the line, farmers, politicians, and environmentalists battled over how best to beat back the bugs.

Check out this video, produced by Retro Report, for a closer look at this historical event.

Questions

What were the different options to control or eradicate the Mediterranean fruit fly?

Bill Van Niekerken, "The Medfly invasion - how a tiny insect upended Bay Area life decades ago," San Francisco Chronicle Nov. 28, 2018

The 1960s represented a time of rapid technological change. The increasing number of machines being used in farmwork meant that the physical number of laborers needed to harvest and plant a field was significantly reduced. Instead, farmers increasingly only needed to hire machine operators.

Mechanical Tomato Harvester, 1965

In 1965, California had 63 total tomato harvesters operating throughout the state. The introduction of mechanical harvesters revolutionized the tomato industry, but also caused tension between farm workers and owners. Farm workers believed that they would lose their jobs because of the new harvesters—however, the introduction of mechanized harvesters boosted production enough that new opportunities for employment in field work, transportation, and processing offset the lost jobs as harvesters.

The machine harvester averaged 0.35 tons of tomatoes per hour; a good hand picker averaged 0.19 tons per hour. The average machine cost per ton of tomatoes picked was $9.84 per ton, while hand picking cost approximately $17 per ton.

Questions

What types of jobs were created as a result of the introduction of the tomato harvesters?

Andrew Schmitz and Charles B. Moss, "Mechanized Agriculture: Machine Adoption, Farm Size, and Labor Displacement," AgBioForum, 2015

Lettuce Industry Changes

Head, leaf, and romaine lettuce are traditionally individually wrapped for the fresh market and are hand harvested. As the agricultural industry moved towards mechanization, the idea of harvesting lettuce via mechanical means presented an issue because lettuce crops do not mature at the same time, so mechanical harvesting would result in major losses.

When the Bracero Program legally ended, lettuce producers were increasingly concerned about the availability of labor for planting and harvest. Baby leaf lettuce was determined to be suitable for mechanical harvest, and the University of California began researching and developing a mechanical lettuce harvester that would be capable of identifying mature lettuce and harvesting just those mature plants.

However, research on a machine capable of selectively harvesting lettuce stopped due to legal issues; instead, the once-over baby leaf lettuce harvester would be used heavily throughout the 1990s.

Questions

What are the challenges of harvesting leaf lettuce?

Is the development of machinery capable of selective harvest practical?

Andrew Schmitz and Charles B. Moss, "Mechanized Agriculture: Machine Adoption, Farm Size, and Labor Displacement," AgBioForum, 2015

Dairy Production Increases, 1975

In 1975, California was the number two dairy producing state in the country, with a total of 10,853 million pounds of milk and 9.4% of the country’s production overall.

Questions

What are the other top dairy producing states?

Do these states have anything in common?

Don P. Blayney, "The Changing Landscape of U.S. Milk Production" United States Department of Agriuclture Statistical Bulletin June 2002

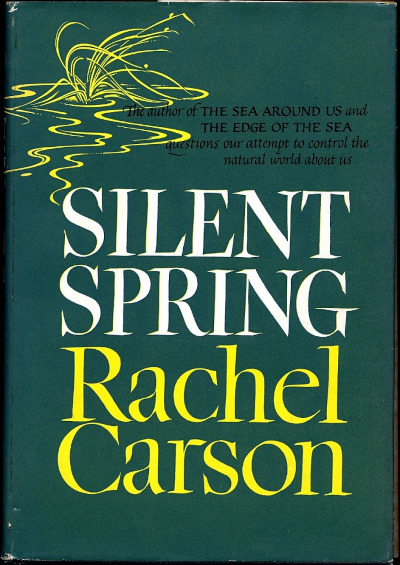

As consumers became increasingly aware of food production, they began researching the pesticides and other chemicals used in agriculture. Rachel Carson's Silent Spring presented the effects of indescriminate use of pesticides and urged all humans to consider their impact on the environment. Agriculturalists, unaware of the potential damages of the pesticides they had been using, responded to legal regulations and restrictions with new and increasingly innovatieve ways to control pests without causing environmental damage.

Ban on DDT, 1972

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) was an insecticide used in agriculture. The U.S. banned DDT in 1972 due to negative effects on the environmental, wildlife, and human health risks. Today, DDT is classified as a carcinogen (a cancer-causing agent) by U.S. and international authorities

Questions

What were the dangers of DDT?

Center for Disease Control

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson, 1962

Biologist Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was published on September 27, 1962 and documented the negative impacts of pesticide use on the environment. The publishing of Silent Spring is best known for fostering the Environmental Movement, but it also established a need for federal involvement in environmental safeguarding, it rekindled awareness in public health, and is still used as a precedent today as we face current challenges regarding the environment. In the decades immediately following the publishing of Silent Spring, federal and state laws and agencies would broaden regulations around pesticide use.

Questions

How did Silent Spring impact the agriculture industry?

How did it impact society as a whole?

What movement was born from Rachel Carson's work?

Rachel Carson, "Silent Spring - I," The New Yorker, June 16, 1962

Environmental Protection Agency, 1970

The Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, was founded in 1970 as a response to increasing concerns over human impacts on the environment. Throughout the 1970s, the EPA became responsible for setting standards and upholding regulations as Congress passed a multitude of Acts and Amendments, including:

-

The Clean Air Act

-

The Clean Water Act

-

Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act

-

Safe Drinking Water Act

-

Toxic Substances Control Act

-

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act

These regulations and industry standards have put limitations and restrictions on how and where agriculture is practiced in the state.

California’s own Environmental Protection Agency was established in 1991.

The list linked here outlines specific protections and standards set by the EPA as they apply to the agriculture industry.

Questions

Research one of the listed Acts and Amendments and summarize its main points.

United States Environmental Protection Agency; CalEPA - California Environmental Protection Agency

The United Farm Workers of America was established in 1962 by Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, Gilbert Padilla, and other leaders. Made up of the combined National Farm Workers of America and the Agricultural Workers Association, the UFW represented one of the first workers’ unions in California to cross cultural and racial boundaries and stand as a united front of farm laborers.

Larry Itliong, 1929-1977

Larry Itliong was a Filipino immigrant who arrived in the U.S. in 1929. He moved around the country to find work, usually taking jobs on farms picking produce or in canneries. Itliong’s experience with poverty and racism motivated him to want to become a lawyer, but those same issues also limited his access to education. Itliong would not become a lawyer but instead became involved in labor activism.

Itliong recruited thousands of new members for the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) and was asked to lead the Delano Grape Strike. During the early days of the strike, Itliong contacted Cesar Chavez to request that the Mexican farmworkers join the strike. In 1969, AWOC and NWFA merged to become the United Farm Workers, or UFW. Itliong died in 1977 after battling Lou Gehrig’s disease.

Cesar Chavez rose to fame as a labor activist, but the actions of his peers Larry Itliong and Dolores Huerta, along with many others, significantly contributed to the successes of the UFW and associated unions.

Questions

What motivated Larry Itliong to become a labor activist?

Why are Cesar Chavez's accomplishments more well-known than Larry Itliong's?

Smithsonian Magazine, July 24, 2019

Cesar Chavez, 1927-1993

Cesar Chavez was born on March 31, 1927 in Arizona. His family moved to California in 1939 and settled in San Jose. Chavez believed that, in order to break the cycle of poverty, it was necessary for all of the children in his family to graduate high school and go to college. However, his experience in school was less than satisfactory, between the strict rules against speaking Spanish in school and the segregation laws that prohibited students of color and white students from attending the same schools.

Education and the migrant farm laborer lifestyle were so incompatible that Chavez’s goal of continuing school was simply out of reach. In 1942, Chavez graduated eighth grade and became a migrant farm worker. After briefly serving in the U.S. Navy, Chavez joined the Community Service Organization; his first experience in activism involved voter registration.

In 1962, Chavez and his peers formed the National Farm Workers Association and began fighting for farm workers’ rights, generally better pay and safer working conditions. Chavez repeatedly underwent hunger fasts in order to draw attention to the cause and demonstrate that the union’s goals could be accomplished without violence.

Chavez continued fighting for farm workers’ rights until his death in April 1993.

For more on Chavez’s life and accomplishments, click here.

Questions

What prevented Chavez from accomplishing his educational goals?

What was Chavez's unique method of drawing attention to the cause?

United Farm Workers

Dolores Huerta, 1930-

Dolores Huerta, born April 10, 1930, grew up in Stockton, California. After completing high school, she attended University of the Pacific’s Delta College to earn a teaching credential. As a teacher, she became increasingly aware of the income disparity affecting California families and got involved with the Stockton Community Service Organization before founding the Agricultural Workers Association. After meeting Cesar Chavez, Huerta’s organizational and speaking skills became increasingly important as their National Farm Workers Association grew.

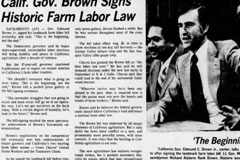

Dolores Huerta was instrumental in many of the NFWA successes, including the Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975. However, Huerta and Chavez occasionally butted heads over feminism and women’s liberation issues.

Dolores Huerta continues her activism work now, working with the Dolores Huerta Foundation to fight for equality and civil rights. To learn more about Dolores Huerta, click here.

Questions

How did Huerta's original career path influence her involvement in activism?

Dolores Huerta Foundation

The California Aqueduct is one of the largest channel aqueduct systems in the world. Its canals, tunnels, and pipelines transports water from the Sierra Nevada Mountains and the valleys of Northern and Central California down to Southern California. Construction on the aqueduct began in 1963 and the first deliveries of water reached the San Joaquin Valley in 1968. In total, the aqueduct stretches over 400 miles across the state. Today, the California Aqueduct serves some 27 million people and 750,000 acres of farmland.

Water Education Foundation (watereducation.org)

The Bracero Program ended on December 31, 1964 when Congress voted to end the program. The program ended for many reasons, including the dramatic mechanization of agriculture practices, economic evidence that employing Braceros reduced the wages of U.S. farm workers, and belief that ending competition in the fields between Braceros and U.S. farm workers would benefit Mexican-Americans.

During the 22 years of the Bracero program, approximately two million Mexicans worked legally on U.S. farms, and at least 100,000 became legal immigrants when their employers sponsored them for immigrant visas in the late 1960s.

Library of Congress ; "Braceros: History, Compensation," from Rural Migration News, April 2006

The Williamson Act, or the California Land Conservation Act of 1965, enables local governments to enter into contracts with private landowners for the purpose of restricting specific parcels of land to agricultural or related open space use. In exchange, landowners receive property tax assessments that are lower than usual, as they are based on farming and open space uses instead of full market values.

The motivation behind the Williamson Act was to promote voluntary land conservation, especially for agricultural uses. The tax relief benefits were intended to keep the land from being developed for non-agricultural means (housing or other industries).

"Williamson Act and Open Space Easement in Santa Clara County," Santa Clara County ; California Department of Conservancy

Farmworkers remained unprotected by many federal and state labor laws and protections. Farm labor unions worked to organize strikes against specific industries, farm owners, or companies. Strikers faced violence, the loss of their jobs, and discrimination for participating, and strikes were not guaranteed to work, as farm operators could sometimes find replacement workers. In some cases, labor strikes were an effective bargaining tool.

Delano Grape Strike, 1965-1970

On September 8, 1965, Filipino-American grape workers began their strike against Delano-area table and wine grape growers, protesting poor pay and working conditions. These workers asked the National Farm Workers Association (led by Cesar Chavez), to join their strike. On September 16, 1965, the NFWA voted yes.

This strike was a marked change from previous farm workers’ strikes, in both its length—five years—and its conditions. Strikers took a vow to remain nonviolent, and received support from other labor unions, church activists, students, and civil rights groups.

The strike also turned into a full boycott against table grapes. The focus of the boycott moved from the farms to the cities, where the protestors could ask for help from consumers. Chavez believed that if the consumers knew about conditions in the field, they would respond by supporting the boycott. And many did by refusing to purchase and consume table grapes.

Eventually, the industry could take no more, and the growers came to the table. In July of 1970, most of the major growers in the Delano area agreed to pay grape pickers $1.80 an hour (plus 20 cents for each box picked), contribute to the union health plan, and provide safer working conditions.

Questions

What motivated the farm laborers to strike?

How did the UFW effectively "win" the strike?

United Farm Workers, National Park Service, & Digital Public Library of America

Salad Bowl Strike, 1970-1971

The Salad Bowl Strike was actually a series of strikes, boycotts, and mass pickets that began in August 1970 and was the largest farm worker strike in American history. Lettuce growers lost $500,000 a day as shipments of fresh lettuce nationwide virtually ceased.

Cesar Chavez and his United Farm Workers (UFW) intended to organize a strike against lettuce growers who would not negotiate contracts with farm workers for decent wages and working conditions. Most Salinas Valley growers did not want the UFW involved, so they signed sweetheart agreements—agreements favorable to the farmers, not the laborers—with the Teamsters Union. Approximately 10,000 Central Coast farm workers respond by walking out on strike. Conflict between the UFW and the Teamsters continued to escalate as the UFW used the boycotts to convince some large vegetable companies to abandon their Teamster agreements and sign UFW contracts.

On November 4, 1970, the Hollister office of the UFW was bombed, and in early December, Cesar Chavez was arrested. The Salad Bowl Strike officially ended on March 26, 1971 when the Teamsters and the UFW signed a new contract, giving the UFW rights to organize field workers. However, relations between the Teamsters and the UFW would continue to be tense and occasionally violent.

Questions

How did the Salad Bowl Strike begin?

What were the issues between the farm workers and the Teamsters Union?

"Union Office is Bombed" New York Times, November 5 1970 ; "Labor: From Fruit Bowl to Salad Bowl," Time Magazine, Sept. 14, 1970

By the 1960s and 70s, the farm labor force is mostly comprised of immigrants, primarily, though not exclusively, from Latin America. Farmworkers remained unprotected by many federal and state labor laws. The UFW and other farm labor unions worked to develop relationships among workers and employers and develop contracts to require protections for workers.

California Agricultural Labor Relations Act, 1975

In 1975, the California legislature passed the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act, establishing the right for farmworkers to use collective bargaining in the state. The act became necessary after the formation of the UFW and ongoing violent conflicts between farmworkers and other employees of the farming sector (foremen, truck and transport drivers, and landowners). California was the first state in the country to legalize collective bargaining for farmworkers. The goal of the act was to ensure peace in the fields by preventing injustice and discrimination in farm labor employment. The Act created the California Agricultural Labor Relations Board (ALRB) to conduct and certify representation in elections and to investigate unfair labor practices.

Questions

What did the Agricultural Labor Relations Act do for farm workers?

What led to the passing of this Act?

Agricultural Labor Relations Board, CA.gov ; Herman M. Levy, "The Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975" Santa Clara Law Review, Jan. 1, 1975

Short-Handled Hoe Outlawed, 1975

The short-handled hoe, with a handle of 10-12 inches, required workers to spend the entirety of their shift in the field bent over while working. When used properly, the tool resulted in frequent injuries and chronic back pain.

Although farm workers began protesting the short-handled hoe in the 1920s, the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl migration put a stop to protests because any job, regardless of the pain or inconvenience, was needed, and farm workers were easily replaceable.

Fifty years later, in the 1970s, the United Farm Workers fought to eliminate the short-handled hoe. In January 1975, California was the first state to ban the tool; the California Supreme Court ruled that the tool was dangerous and “causes injury, immediate or cumulative, when used in the manner in which it was intended.”

Questions

Why did farm owners and supervisors continue the use of the short-handled hoe when there was an alternative option?

Why did farm workers protest the continued use?

"Weeding California Fields," Rural Migration News July 1995 ; National Park Foundation ; National Museum of American History

The University of California Master Gardener Program was founded to help create and distribute resources and information to community gardeners across the state. The first Master Gardener Programs were set up in Riverside and Sacramento Counties in 1980.

The Master Gardener Program certifies volunteers in different gardening topics, including integrated pest management, irrigation techniques, and basic botany. The program requires its members to complete 50 hours of work and volunteer time, and asks for certified Master Gardeners to continue training and volunteering annually.

The Master Gardener Program helps California agriculture by supporting backyard agriculturalists. Some might sell their produce at Farmers Markets, or even produce specialty crops and sell them to grocery stores. In addition, Master Gardeners develop new techniques and methods to grow their crops that may benefit large-scale farmers.

University of California Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources

For several decades after World War II, population growth was central to California’s large cities including Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, and Sacramento. Agricultural production was pushed further and further away from the centers of population, but was not negatively impacted. Dairies, citrus growers, and fruit orchards alike moved into the Central Valley, an area unpopular for settlement but rich in agricultural resources, including natural water sources and good quality soils.

However, during the 1980s California’s population began spreading further out. The growth of the suburb, a residential community within commuting distance of a city, caused increasing competition between farmers and residential development companies over available land. Over the course of the 1980s, the population of California’s Central Valley increased by 30% as commuting long distances to work became more commonplace, industries in the region grew, and city-dwellers desired a more sedate and private suburban lifestyle.

The changing demographics of the Central Valley have led to conflicts over land use, air quality, water resources, and environmental factors.

"Keeping the valley green: A public policy challenge," California Agriculture May 1, 1991

California Farmland Conservancy Program, 1995-

According to the state Department of Conservation, California loses one square mile of farmland every five days, and 70% of that land is quality farm land with water access and rich soil. The California Farmland Conservancy Program, or CFCP, is a statewide grant program that helps protect farming and ranching operations in agricultural areas. The program is meant to prevent farmers from selling their lands to residential or industrial developers and works closely with land planning agencies to conserve agricultural land.

To learn more about changes to California’s Farmland, check out the California Department of Conservation’s report, most recently updated with data from 2018.

Questions

What necessitated the development of the CFCP?

What does the map, linked above, illustrate?

California Department of Conservancy

When Congress passed and the president signed into law the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, the result was the first major revision of America’s immigration laws in decades. The law seeks to preserve jobs for those who are legally entitled to them—American citizens and aliens who are authorized to work in the United States.

Although the act was meant to tighten immigration, it also offered legalization, which led to lawful permanent residence (LPR) and prospective naturalization to undocumented migrants, who entered the country prior to 1982. Farm workers who could validate at least ninety days of employment also qualified for lawful permanent residency.

Approximately three million people, most of them from Mexico or other Latin American countries, gained legal status through the act. California’s large population of migrant workers benefited significantly from the act, gaining legal protections from discrimination and unfair work conditions. In addition, legal status allowed migrant workers to get promotions, buy property, apply for loans, and obtain health insurance.

Library of Congress